A lost Yiddish opera complete, and in performance, at last

Jan Massij’s “David and Bathsheba.” by Wikimedia Commons

One of the only known pre-Holocaust Yiddish operas performed in Europe had a rather shabby debut.

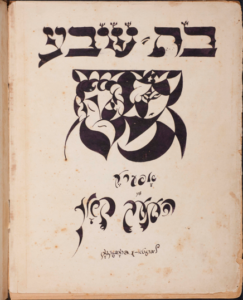

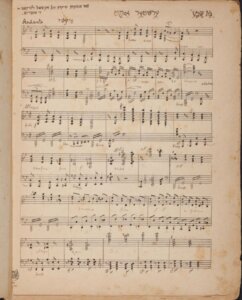

When it premiered May 24, 1924, at Warsaw’s Kaminsky Theatre, its composer, Henech Kon, had to accompany the performers on piano — and sing the bass part himself. It wasn’t quite the presentation he had in mind. But Kon would go on to bigger things, composing music for the classic Yiddish film “The Dybbuk.” His opera “Bas Sheve” (Bathsheba), about King David’s sinful affair with the titular wife of his general, would be one of many lost compositions, if one that had a certain prestige.

“It was kind of like it was a chimera,” said Yiddishist Michael Wex, the bestselling author of “Born to Kvetch.” “It was one of those things that was always schlepped out as a ‘What do you mean there is no high culture in Yiddish? There was even an opera in Yiddish.’”

No one could say much about how the opera sounded until 2017, when researcher Diana Matut learned that the Yale University Library bought a handwritten score of “Bas Sheve” at auction. After over 90 years, the Yiddish world now had access to Kon’s melodies and the words of his librettist and regular collaborator, the influential playwright, poet and director Moyshe Broderzon.

Well, almost.

Matut, a lecturer in Jewish studies at the University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, sent the manuscript to composer Joshua Horowitz to orchestrate it for a performance at Yiddish Summer Weimar. But Horowitz ran into an immediate problem — there were 16 pages missing. And not just any pages, but the climax of the entire work.

Horowitz reached out to Wex to write the missing text and now, their version will play its first North American performance at the Ashkenaz Festival, the annual Jewish art and culture festival in Toronto. on Aug. 31.

Speaking over Zoom, Horowitz and Wex say they weren’t daunted by the task of filling in the missing pieces, though it took some trial and error. It’s not clear what Broderzon or Kon had in mind for the plot during the missing chunk, and the Book of Samuel, where the story is recorded in the Bible, didn’t offer any guidance. After consulting some midrashim, Wex decided to insert a sequence where David sees the ghost of Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, whom David sent to his death on the frontlines.

If figuring out the story posed a problem, so was divining what was going on musically. Heeding Matut’s advice that the new music should be treated like a “museum restoration” of a restored painting, Horowitz’s new movements contrasted somewhat with Kon’s, while borrowing from some of his other work, notably his song “Yosl Ber,” about a soldier, and a niggun from “The Dybbuk.”

“Composers often recycle their own work, so I thought I’d recycle it for him,” said Horowitz, whose own works include the one-act opera “Lilith the Night Demon.” “And I used a couple of other styles that Kon didn’t use, slightly more contemporary styles for Kon’s time.”

Matut and Horowitz noted that, while Kon was writing in the wake of Stravinsky and Schoenberg, “Bas Sheve” is working within a different tradition.

“It’s very much Western, early 20th century – it has moments of late Baroque,” Matut said. “It’s high romantic.”

Given that sensibility, it’s perhaps not surprising that, while called “Bas Sheve,” the opera doesn’t spend much time grappling with the title character’s inner life. In filling out the libretto, Wex didn’t want to interfere with what Broderzon and Kon had written, and so opted for David’s own struggle with his conscience.

Wex, who is also putting on a cabaret inspired by Broderzon at Ashkenaz, and Horowitz, who writes his own operas, admit that “Bas Sheve” is not the greatest opera you’ve never heard. Nonetheless, they value it as a vital piece of the canon that had been missing for too long and can correct some misconceptions about what Yiddish culture is capable of.

“An opera like this, it’s important in part as a sign,” Wex said. “Yeah, it can be done. It has not only been done, it was done when your grandfather was a child. It’s been around a long time.”

“Bas Sheve” debuts at the Ashkenaz Festival Aug. 31, 2022. More details can be found here.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that “Bas Sheve” was the only known pre-Holocaust Yiddish opera performed in Europe. It has been updated to reflect the fact that there were others, notably Samuel Alman’s “Melech Ahaz,” which toured England.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30