San Francisco, early 1962. For Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete – who would have turned 100 last month – a night would hardly go by without a gig in the Tudor Room of the Sheraton Palace hotel. Bossa nova, seen as a classy background music in hotel dining rooms, was in high demand – but hired to play at cocktail hour, Sete would often go ignored by the audience of thirsty diners. Things changed when trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie recognised Sete and his guitar, the pair having met in Rio de Janeiro a few years earlier.

Gillespie was astonished, so much so that he would return to the Tudor Room with pianist Lalo Schifrin to witness what this little-known musician was capable of. “He was sending a message. It was a message very intense,” Schifrin later said.

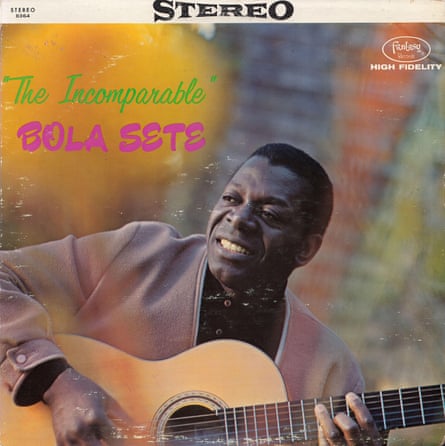

Sete would soon play on Gillespie’s iconic album New Wave! and shone at the Monterey jazz festival, but he went further still. Now considered a forefather of New Age music, Sete also stood out for his hypnotic performance style, unparalleled guitar technique, and ability to translate the music of the world (from Brazil to India) to his singular jazz language.

The late John Fahey, visionary American folk and blues guitarist, said listening to Sete for the first time was “a turning point … I couldn’t sit still. I’d never heard anything like it since Charley Patton, and this was better. I was transformed, purged – I was not the same.” Carlos Santana, meanwhile, affirmed that the “holy trinity” of guitar playing consisted of Wes Montgomery, Gábor Szabó, and Bola Sete. In a testimonial for a posthumous Sete album, Samba in Seattle, Santana said that the Brazilian musician was “an orchestra by himself”.

Eventually, he would come to be sampled by the likes of Destiny’s Child and A Tribe Called Quest, but his journey began on 16 July 1923, in Rio de Janeiro’s port area. Djalma de Andrade (his birth name) was raised by highly musical relatives – many of whom played music, mostly samba and choro, for a living. De Andrade started venturing on to the guitar at three; at six, he gained a cavaquinho (typical samba string instrument) from his mother.

She died when Sete was a child, and aged 10 he was adopted by a middle-class family who helped him to study classical guitar at Rio’s National School of Music. There, the guitarist formed his first Brazilian music ensemble, where, as the only Black member, he earned the nickname Bola Sete (an allusion to the brown billiard ball).

During his professional years in Brazil in the 1940s, Sete played choro with masters including Dilermando Reis, Garoto, and Radamés Gnatalli; learned folk music elements from his time spent in Rio’s countryside; and got inspired by foreigners such as Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian. After years of performing with different ensembles across Europe and South America, he settled in San Francisco in 1959. Having played with pianist Vince Guaraldi from 1963 to 1966, he was named guitarist of the year by jazz bible DownBeat magazine and “one of the most innovative and eclectic guitarists in jazz history” by Leonard Feather’s Encyclopedia of Jazz in the Sixties.

“He was ascending in prominence among jazz critics and lovers, while the rest of the Brazilian musicians [who then resided in the US] were quickly falling in prestige,” says ethnomusicologist Kaleb E Goldschmitt. “He’s the one who escaped the ‘fad’ discourse.”

This fad was the 1962-3 period when bossa nova broke out of the upper middle-class bubble in those high class hotels and reached a much wider public. By 1964, most Brazilian bossa nova-related musicians were no longer considered cool, but jazz fans and the media were still raving about Sete – “[jazz guitarist] Charlie Byrd was able to identify his sound with a blindfold on,” says Goldschmitt – long before bossa nova’s second wave came with the Getz/Gilberto album and The Girl from Ipanema hit.

“He used fingerstyle technique, which allowed him to play very independent lines, like a piano player,” says jazz guitarist Scott Hesse, also a music professor at DePaul University in Chicago. “His pianistic approach just wasn’t something that a lot of guitar players were doing to that level at that time.”

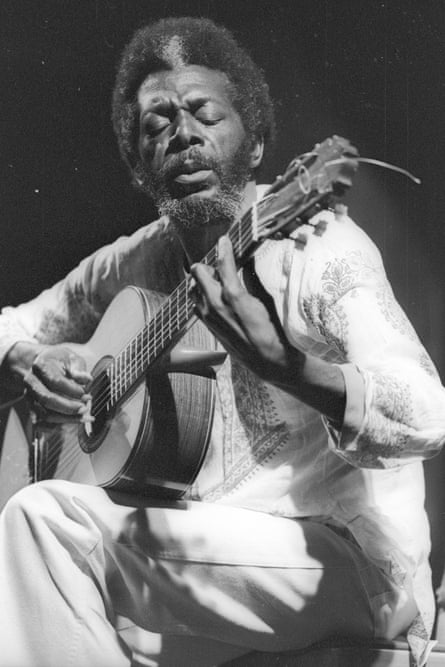

He gave that technique (a result of studying his Ramírez guitar in front of the mirror for many hours) a powerful expressiveness, particularly on stage. “He could actually read a room and understand how to make it a meaningful experience,” says Hesse, recalling that 1966 Monterey jazz festival performance. “From the first note, he had the people in the palm of his hand and then took them on a journey throughout the entire set.”

According to his widow, Anne Sete, “he was quiet most of the time, but had a magnetic presence that attracted others. Sometimes he would walk out on stage with his guitar and the audience would give him a standing ovation.” Anne and Sete met in 1965 when they became neighbors in Sausalito: “He radiated a sense of peace and love.”

Having played numerous gigs with Sete in the late 1960s, Brazilian drummer Chico Batera recalls how their shows always went beyond “mere” bossa nova and jazz repertoire. “There was a moment when the bassist and I would leave the stage, and Sete stayed to solo [Brazilian composer and classical guitarist] Villa-Lobos on his guitar.” Batera, who also played with Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, adds: “Sete made history, increasing the prestige of Brazilian music among jazz lovers.”

Sete’s aim to expand music boundaries became even more sophisticated after the 1970s, when, dedicated to solo guitar studies, he opened dialogues with cultures as diverse as Spanish folk music, samba, north-eastern Brazilian baião, blues, and Indian music. Ocean (1975) pre-empts “a lot of what happened in the New Age music from the 1980s and 1990s,” Hesse says.

Before his death in 1987, Sete’s last works reveal a highly spiritual musician, inspired by the philosophy of yoga. “After Bola mastered the full lotus position, he told me that musical information could come in without any obstructions. Music, he said, required him to get out of the way,” says Anne, recalling that they loved going to the Marin County beaches and practising yoga on the sand.

Today, Bola Sete is unfamiliar to most North American and even Brazilian audiences. “People didn’t really know how to categorise him because he brought in so many different influences,” Hesse argues, while Goldschmitt affirms that guitarists have never really been acclaimed throughout jazz history: “Pianists are the most respected, and then brass players. The flute is way down at the bottom. And the guitar? Way, way lower.”

Nevertheless, Sete is present in ways people do not always realise. According to Hesse, “there are things Bola did that, at this point, are a part of every guitarist’s technical repertoire. He was way ahead of his time.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion