The last days of August on the Isle of Wight, the weather fair, the island relishing the height of summer holiday season. If there was trepidation among the local community regarding the imminent music festival – the island’s third – it was hoped it might be quelled by a site relocation to Afton Down, a stretch of farmland near Freshwater Bay where the hippies and freaks could revel far from the holidaymakers, retirees and yachters.

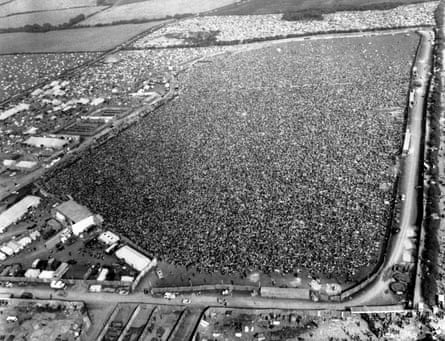

It was a ticketed event, promising Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, Joan Baez, Free, the Who, Sly and the Family Stone and the Doors, and, going on the previous year’s success, 250,000 attendees were expected. Quickly, however, more than 600,000 people flocked to the festival ground, knocking down security fences, setting up their blue and orange tents on a hill overlooking the site, and building an encampment out of hay bales in an area they named Desolation Row.

The mood was different this year: the crowd was disgruntled by the cost of tickets (the equivalent of about £40 today), the increased security measures, and the rumoured steep fees of the performers, all of which seemed at odds with the era’s anti-capitalist movement. Fights broke out, objects were thrown, and a lot of bad acid was taken. In desperation, the organisers threw up their hands and declared it a free festival.

It did not help that several of the performers rolled up to Afton Down in particularly ostentatious modes of travel: Rolls-Royces and sports cars that flaunted their new-found wealth. Donovan arrived in an antique stagecoach that would also serve as Joni Mitchell’s dressing room.

Mitchell had been scheduled to perform in the evening, but it was mid-afternoon when she walked on to the stage in a long yellow dress and squinted at the crowd. “It looks like they’re making Ben Hur or something,” she said, and played The Gallery. The crowd jeered. Some years later, asked why she had agreed to move her set time to that less alluring hour, Mitchell seemed resigned to her fate: “I have a feminine cooperative streak,” she said. “So I said yes. And they fed me to the beast.”

Then in the ascent of her career, she moved between acoustic guitar and piano to draw on material from Clouds, Ladies of the Canyon, and the yet-to-be-released Blue. But the atmosphere was curdling, and Mitchell seemed ill at ease. She began the song Chelsea Morning, then quickly muttered that she did not “feel like playing that one” and began afresh. She was, as the Guardian review at the time noted, “harassed by a reckless crowd”, facing heckles, interruption, shouts; a flailing man on LSD, another playing bongos. A doctor was summoned for someone. Even her efforts to enjoin the audience in singing the chorus to her hit Woodstock seemed to fall flat.

When the song finished, a man named Yogi Joe, who had been sitting near Mitchell’s piano (and had taught the singer in her first yoga class at the caves of Matala on Crete) commandeered the microphone and began a speech about the community camped up on Desolation Row before being hauled away. “Let him speak!” called the crowd. “Let him speak!”

Mitchell’s 12-song set would prove a pivotal moment in the festival. Several times she beseeched the crowd to quieten down, gently at first, imploringly: “It really puts me uptight and I forget the words and I get nervous,” she told them three songs in. “It’s really a drag, and so I don’t know what to say. So just give me a little help, will you?” Later she grew steely. “Give us some respect,” she said plainly.

She gathered herself for renditions of My Old Man and Willy, and then the five-song run that followed – moving through A Case of You, California, Hunter, Big Yellow Taxi and Both Sides Now – proved so electrifying, so transformative, that the crowd acquiesced. This is about music, this stretch of her set seemed to say, not the camp on the hill, or the curry powder sold as marijuana, or the kaftans and capes or even the reviled capitalism. Just music.

This would be the last event of its kind on the Isle of Wight for 32 years. But it marked, too, a shift in the spirit of festivals. They would require more organisation, more forethought, more security, and there would develop, too, more of a divide between audience and performers.

That August in Afton Down, that new sense of division seemed clear. It was there in the have-tickets and have-not, in the sight of Yogi Joe, silenced and dragged off stage, in the stagecoaches and drug busts and the fights in the crowd. “There’s a dankness and gloom about this festival,” one attendee told the New York Times as he waited for the ferry at Yarmouth. “Don’t tell me there was any kindness or sharing or love,” added another. “It was cold, man, cold, and I didn’t like it one bit.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion