Until last week, Santano Viperillo was just a music producer and promoter living in Naples. But on 30 December, everything changed and he became a potential criminal thanks to a new government crackdown on illegal raves. If Viperillo (who goes by a pseudonym) continues to organise the parties he has been running since the 90s, initially as part of the famed 1990s Neapolitan rave crew United Tribes, he could face up to six years in prison.

The so-called “decreto anti-rave” was the first bill proposed by Giorgia Meloni’s rightwing coalition when the prime minister took office in October. Now officially approved by parliament, it makes organising raves a specific crime punishable with three to six years of jail time, fines of up to €10,000 (£8,900) and the confiscation of equipment. The new statute also allows the surveillance of groups who are suspected of holding these unauthorised events, including tapping their phones.

Nicolò Bussolati is a lawyer who often defends rave organisers. He says this new law stands to “ruin the lives” of his clients, many of whom are still in their 20s. Rave organisers, he says, “can now be punished with a very high penalty similar to that of a criminal conspiracy”: the minimum punishment is six times higher than kidnapping, which carries a six-month minimum sentence. “This is a clear statement to citizens that holding a rave is one of the worst crimes you can commit,” he says.

Raves have been going on for decades in Italy without being seen as a major issue. But in the past few years they have become a hot-button topic, with the media fuelling negative campaigns against them and conservative politicians demonising ravers after newspapers linked a party in Valentano, a town in central Italy, to the fatal drowning of a man in a nearby lake.

The culture has roots in the early 1990s, when raves were organised in Turin, Milan, Bologna and Rome, says Pablo Pistolesi, a DJ and producer known as Pablito El Drito who has written several books on the subject. “Back then they were a niche phenomenon,” he says, “frequented by people from other subcultures such as punk, hip-hop and squatters.”

The phenomenon grew after 1994, when some British rave crews – fleeing the crackdown on illegal raves at home – moved to France and then to Italy. Spiral Tribe, the London collective that had faced a trial described as “one of the longest and most expensive cases in British legal history”, became a driving force on the Italian scene, introducing the travelling culture and a new aesthetic.

“Before that, the parties were organised locally – those from Rome play in Rome, those from from Milan play Milan and so on,” says Pistolesi. “That changed with the Spiral Tribe: they also brought the all-black and dreadlocks look.”

Italy’s rave scene grew further in the early 2000s thanks to the dissemination of information online: the largest rave ever recorded was the Pinerolo “teknival”, held in the western Alps in 2007 and attended by 40,000 people. Most raves were already technically illegal – Italy has long had a law against trespassing of private property and requiring permits for the use of public spaces – but they tended to pass under the radar.

That changed in August 2021, when around 100 crews from across Europe organised a teknival in Valentano, held on land owned by a local entrepreneur who was then a candidate with the Brothers of Italy, the party led by Meloni that has neo-fascist origins. During the course of the event, a young British citizen, Gianluca Santiago Camassa, drowned in a nearby lake. According to his father, Camassa intended to attend the party but died beforehand in an unrelated swimming accident; nevertheless the Italian media connected his death to having attended the rave.

The story sparked media hysteria. Soon more stories appeared about rapes and another death at the same festival, none of which were supported by evidence or on-the-record witnesses. Newspapers published a report about a woman giving birth in an ambulance at the party based on a single anonymous quote given to a news agency. Eventually the party was branded il rave degli orrori – the rave of horrors.

“After the Valentano rave, the media campaign against us started, they talked about dead dogs, of raped girls, but it was all made up,” says Dj Orz, a member of Kernel Panik, a key Italian rave crew that has been active since 1998.

after newsletter promotion

In October 2022, a smaller rave, known as the End of the Rave, was held on the outskirts of Modena. It was the first to take place under the new rightwing coalition. Having come to power the previous month, the government made an example of the event: interior minister Matteo Piantedosi ordered the police to stop it by any measures necessary and they negotiated the peaceful halt of the party soon after. It was the same weekend that the government took no action against a march by more than 2,000 fascist sympathisers to Mussolini’s crypt in Predappio.

That month, the government presented its anti-rave bill. Giulio Centemero, a MP from the League, a far-right party in the coalition, claims that the law is “necessary to upgrade our system of protections of private property and public safety” and argues that a specific law against raves was needed. “In our juridical system there wasn’t an organic definition of illegal rave party. In a civil law system such as ours, it became therefore necessary to codify it.”

A common criticism against the bill is that it allows the use of disproportionate means, such as phone tapping. Centemero disagrees: “These tools are provided by the criminal code. Are they excessive? I don’t think so.”

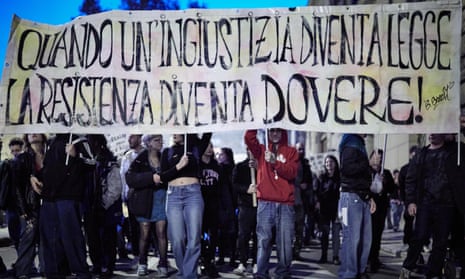

As soon as the bill was presented, rave crews and sympathisers rallied against it, pointing out that it could be used to clamp down on sit-ins and other forms of protest. Using the hashtag #smashrepression, they organised protests in Turin, Bologna, Naples, Rome, Palermo and Florence that brought thousands of people to the streets.

Producer and promoter Viperillo was among them. “For those who have never seen them, raves are places of perdition. But for those who frequent them, they are a place to meet, socialise, make friends,” he says. “This is why it is important to make sure that the government hears the voice of the rave community and all other underground music communities loud and clear.”

Nevertheless, the bill now stands as law. Some Italian ravers are vowing to go on in spite of it. “I’ve been organising raves for 30 years,” says Dj Orz. “For me it’s a lifestyle choice, something that has never changed. They can’t think of stopping the wind.”