Classical musicians will have access to a huge library of interactive sheet music via a groundbreaking app that leading cultural figures say has the potential to revolutionise music-making.

Artificial intelligence experts working with musicologists at a Berlin startup have spent years gathering hundreds of thousands of published scores and creating digital editions of each of them.

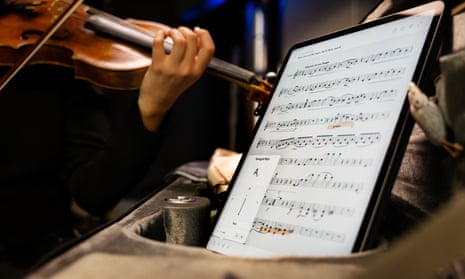

The Enote app will give musicians the chance to interact with sheet music by instantly transposing it, switching between movements or measures, turning pages, changing the size of scores, and printing them on the go.

Boian Videnoff, the chief conductor of the Mannheim Philharmonic and one of Enote’s founders, said he hatched the idea at his kitchen table with his university friend Josef Tufan after mounting frustrations over sheet music publishers’ failure to make the leap into the digital world. Tufan, an IT management consultant, is a co-CEO.

“I had been complaining to Josef about why digitalisation wasn’t happening in the music world, and he was making fun of me having to drag a whole suitcase full of scores with me when I travelled. We decided together to tackle the problem,” he said.

The result, more than five years later, is the world’s first comprehensive library of native digital sheet music.

In an exclusive preview at the company’s offices on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, Videnoff first pulled up a pdf of one of Chopin’s mazurkas on his tablet, the format that musicians have turned to in recent years. “You can zoom in and out but that’s about the extent of it,” he said.

Then he showed a digital version where the musical notation had been – as he put it – “semantically reconstructed” using optical music-recognition technology. He demonstrated how the notation could be transposed by switching within a second from D-major to C-major – something he said would ordinarily take weeks.

Although the app’s official launch has been put off owing to the coronavirus pandemic, Enote has been inundated by musicians throughout the world wanting to become early beta testers. The testers will not have to pay for the app and will contribute to its development.

Other users will be charged €9.99 a month, which will give them unlimited access to the library of around 150,000 scores and all the app’s features. Videnoff said the price point would mean savings for musicians and reduced material costs for orchestras, paying Euros 600 to provide every member with a score of, for instance, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Enote’s main backer is Manfred Fuchs, a music lover and former CEO of a leading industrial lubricant manufacturer, Fuchs Petrolub, who has invested €4m.

Its supporters from the world of music include the baritone Thomas Hampson, the cellist Mischa Maisky, the violinist Lisa Batiashvili, and Michael Barenboim, the violinist and concertmaster of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, who is the son of the conductor Daniel Barenboim and the pianist Elena Bashkirova.

“Everyone in the music world is talking about it and I’m sure we’ll all be using it sooner or later, including my father,” the younger Barenboim told the Guardian. “It will be a gamechanger for musicians. The possibilities are very exciting, especially for the field of music education.”

Enote will initially concentrate on solo and chamber works, from the baroque to the late romantic era. Within the next year it also plans to have a comprehensive orchestral and operatic repertoire, before turning its attention to contemporary classical music, including offering modern composers a platform for their works to reach a wider audience and earn a living.

In Enote’s “engineering room”, historical musicologists, mathematicians, musicians, a musical engraving technologist and AI experts pored over screens full of greened-up static scores in the process of being translated into digital.

As the chief technology officer, Evgeny Mitichkin, explained, the computer has to “learn to recognise and classify everything, from noteheads and slurs, to keys and signatures, before semantically reconstructing them” in a “musically sensible way”.

Although interactive e-readers are a model for Enote, digitalising music is far more complex than digitalising text, Mitichkin said. Compared with the 26 letters of the alphabet, musical notation consists of up to 1,500 elements. “The metadata and the score have to match perfectly,” he said. “It is the first time in history that this matching process is being done. We’re effectively in the process of preserving our cultural heritage as well as democratising access to it.”

The high-powered processors in the next room emitted a rumbling sound which, the team says, sometimes sounds like a Boeing taking off.

There was consensus among the team about which score had been the most complex to digitalise. Gerrit Bogdahn, a drummer turned musicologist, produced the paper score of Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit, considered one of the most demanding piano works of all time, a heady, nervous piece sometimes described as Ravel on drugs.

“Look at bar 122,” he said, showing a thicket of notes and symbols in the Scarbo movement. “Ravels throws in a hairpin, and there are beams crossing the hairpin as well as each other, and the slur is crossing it all from top to bottom in an S-shape.

“This was our Mount Everest,” he said, showing the digitalised result. “Once we’d reconstructed this in digital form, we knew that nothing was beyond us.”