An ’80s song is easier to pick out than a cowboy at a cocktail party, but why? Mostly because what was developing on the technical side of music back then would have previously seemed like science fiction. When the '’80s began four decades ago, few people could have predicted what the advances in recording and instrument technology would bring. But with hindsight in your hip pocket, it’s easy to identify the innovations that defined the pop palette in the age of synthesizers and shoulder pads.

The LinnDrum Machine

In the ’70s, drum machines hadn’t advanced much beyond the buttons marked “foxtrot” and “rhumba”on a home organ console, generating something akin to a pair of chopsticks tapping on a milk carton. Enter the unlikely catalyst, Roger Linn. Linn had actually been a guitarist, playing with rockers like Dwight Twilley and Leon Russell in the ’70s and writing songs for Eric Clapton and others. But he was also an engineer, and he recognized the need for a drum machine you could bring into a recording session without getting laughed out of the studio.

In 1980, Linn’s LM-1 Drum Computer became the first drum machine to use digital samples of real drum sounds, not to mention allowing users to tune the individual sounds and even add a “swing” effect to approximate a human drummer’s feel. It took off immediately, but in ’82 Linn really hit the sweet spot with the LinnDrum machine, a revamp of the LM-1 that knocked 40 percent off its predecessor’s 5K price tag. Soon, Linn’s digital beats defined the sound of the ’80s, from Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax” and Tears for Fears’s “Shout” to Irene Cara’s “Flashdance...What a Feeling” and Dead or Alive’s “You Spin Me Round (Like a Record).”

The Sampler

It doesn’t get more ’80s than the sound of a sampler, but the basic blueprint for sampling actually goes back to the ’60s. Forward-looking keyboardists in the ’60s created orchestral sounds with the Mellotron, whose keys actually triggered reels of tape containing recordings of strings, horns, choirs, etc. In the late ’70s, samplers stored digital recordings of real instruments, not only providing countless sounds at the touch of a key but also allowing users to manually edit those sounds. The first widely used samplers were the Synclavier and the Fairlight CMI, the former starting at around $200,000 and the latter going for a measly $25,000. But by the early ’80s big-name producers were all over them, and soon, less expensive models like the E-mu Emulator and the Ensoniq Mirage spread sampling even further.

Those horn stabs you hear on Yes’s 1983 smash “Owner of a Lonely Heart?” They were sampled from a James Brown record. The exotic bamboo flute on Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer?” It came straight from an Ensoniq sampler. And of course, hip hop as we know it couldn’t have existed without ubiquitous samples like Clyde Stubblefield’s beat on James Brown’s “The Funky Drummer,” heard on countless cuts by everybody from Public Enemy to Run-D.M.C.

Gated Reverb

In 1981, Phil Collins introduced the world to what would become one of the most famous drum breaks ever on his first solo single, “In the Air Tonight.” The break that inspired air drummers worldwide for generations to come owes much of its thunderous power to the innovations of producer/engineer Hugh Padgham. Padgham had actually helped Collins create the huge, explosive sound about a year earlier, along with producer Steve Lillywhite, when Collins was drumming on former Genesis bandmate Peter Gabriel’s self-titled 1980 album. It was achieved by recording the drums in an extremely “live-sounding” room for maximum reverberation and then applying a noise gate that abruptly cuts off the natural reverb, making each drum hit sound like a cannon blast.

The gated-reverb approach to recording drums helped make “In the Air Tonight” an enormous hit, and it became a go-to for the Big ’80s. Naturally, Collins continued to use it both solo and with Genesis. But the sound also put some extra oomph behind Max Weinberg’s slamming beat on Bruce Springsteen's “Born in the U.S.A.,” Tony Thompson’s commanding whomp on The Power Station’s “Some Like It Hot” and “Get It On (Bang a Gong),” and legions of others.

Digital Synthesizers

Everybody thinks of the ’80s as the era of the synthesizer, but for the first few years of the decade, synth technology was still stuck in the ’70s—strictly analog. It wasn’t until Yamaha introduced the DX7 in 1983 that digital synthesizers really took off. The difference between analog and digital synths is that with analog the circuitry is wired to mechanically generate its sounds, and with digital the sounds are computer-generated. Analog synthesizers are generally considered to be warmer and fatter sounding, while machines like the DX7 were sharper and thinner, but capable of a wider variety of tones.

Once musicians started tucking into digital synths, they learned how to use them for everything from bass lines to percussive sounds and just about anything else you can think of. Odds are, if you heard a synthesizer on an album in the second half of the ’80s, it was digital. Steve Winwood’s “Higher Love,” for instance, features keyboard, bass, and horn sounds all generated by digital synths. The punchy bassline on A-ha’s “Take On Me” is a classic DX7 sound. The melody that opens and closes George Michael’s “Father Figure” comes from a Roland D-50. And just about everything but the guitar and drum machine on Tina Turner’s “What's Love Got to Do With It” was generated on a DX7, right down to what you might have mistaken for a harmonica solo.

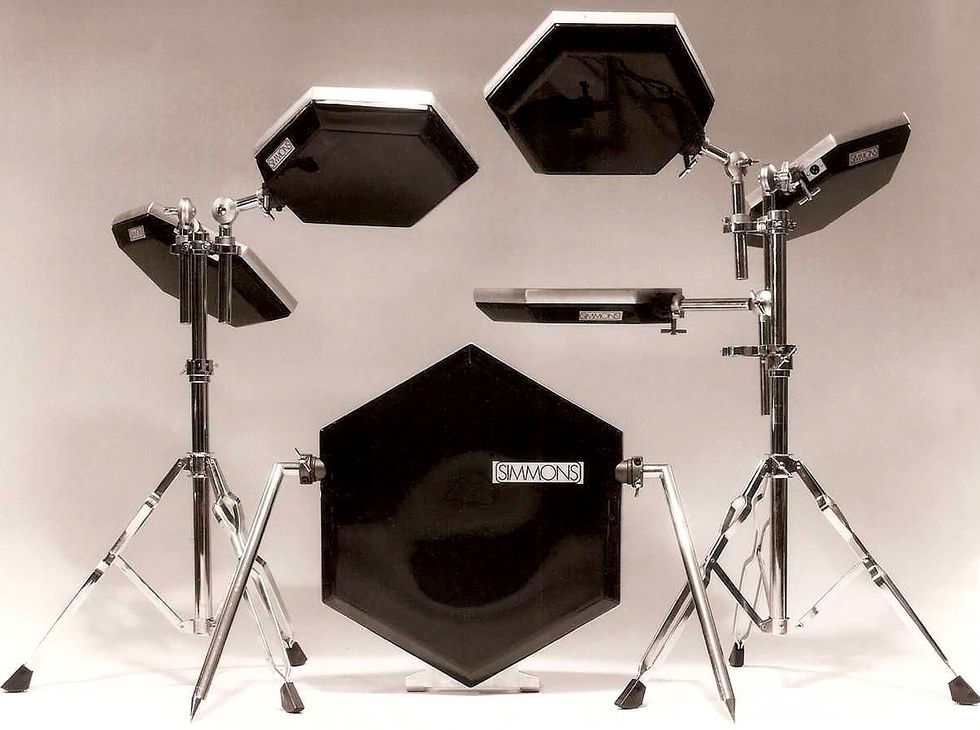

Simmons Drums

For those who sought the big, electronic drum sounds of the ’80s but still wanted to use an actual drum kit, there was the Simmons SDS 5. A series of hexagonal, electronic pads arranged like a conventional drum set, they could be recorded (and processed) in the same way as any other electronic sound source. Each pad bore the tone of a different drum or cymbal, with several options programmed in. The SDS 5, the first full electronic drum kit, hit the market in 1981, created by producer/musician Richard James Burgess with engineer Dave Simmons.

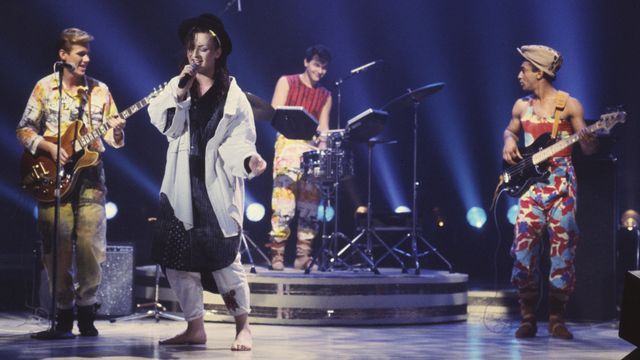

Burgess recalls, “Initially, my only thought was to build this for myself to eliminate open mics on stage and to get a sound that was as powerful and as playable as acoustic drums but that offered a brand-new palette of sounds. What made it special was that it really did substitute for acoustic drums and they looked very different and very cool. The first recording that used it with a drummer playing them was my production of ‘Chant No.1’ by Spandau Ballet.” With its futuristic look, the SDS 5 was a ubiquitous presence onstage and in music videos as well as recording studios. From latter-day Genesis hits like “Invisible Touch” to early Culture Club tunes like “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?” and “I’ll Tumble 4 Ya,” you could scarcely scan an ’80s radio dial without a Simmons kit bursting out.

Watch drummer Bill Bruford of Yes demonstrate a Simmons electronic drum kit (below).