The Changing Sound of Male Rage in Rock Music

Linkin Park introduced new ways of expressing male angst into the mainstream—an evolution that continues today.

At the end of 2017, U2’s Bono made one of his periodic pronouncements about the state of rock and roll. “I think music has gotten very girly,” he told Rolling Stone. “There are some good things about that, but hip-hop is the only place for young male anger at the moment—and that’s not good … In the end, what is rock & roll? Rage is at the heart of it.” He was airing the sort of conventional wisdom you most commonly hear ranted from a barstool: Rock and roll is rooted in virility, and the genre’s decline in popularity represents a worrisome triumph of the feminine. Though such gender anxieties uncannily mirror the ones driving national politics, rock is of course bigger than one gender or one emotion—ask Joan Jett or Courtney Barnett. If angry men loom large in the genre’s history, it’s not because they have tapped into some elemental well of gender-specific sentiment. Instead, they have often made their mark by expanding the boundaries of what anger or sadness, or anger and sadness together, can sound like for guys.

Bono’s comment got me thinking not just about that lineage of sound and sentiment, but about Chester Bennington, the Linkin Park singer whose suicide a year ago this summer I’ve had very much in mind. By some measures the last top dog that rock ever bred, the California group is often spoken of as an embarrassing artifact of George W. Bush–era cultural crudeness. But in hindsight, Linkin Park’s trajectory, and Bennington’s, sheds light on an evolving quest for new ways to express vulnerability. The pop landscape that has emerged may bewilder Bono, but space has opened up for male fury in more malleable forms than ever—and such fury seems to be, for better and for worse, in plentiful supply.

Linkin Park’s product was male rage in a form the entire family could mosh to. (It’s worth noting that sales figures for the band’s 2000 debut album, Hybrid Theory, have been surpassed in the new millennium by no rock album other than The Beatles’ 1.) The guitarist Brad Delson’s cleanly rumbling chords triggered the kind of shiver you might feel while in a dinghy passing an aircraft carrier. Co–front man Mike Shinoda rapped in blocky syllables, his voice a stentorian simplification of the voice cultivated by Public Enemy’s Chuck D. A DJ who went by the name Mr. Hahn threaded in nerdy-cool electronic sounds; the drummer, Rob Bourdon, hammered with comforting steadiness; and a bassist who called himself Phoenix shellacked on an ominous tint.

The most important ingredient was Bennington’s wail and whisper, a volatile fuel to be processed by the others. To revisit the video for the 2001 Linkin Park single “Crawling” is to see his powers at full strength, and his special appeal laid bare. At the outset, a music-box ballerina spins, a woman cries into a bathroom sink, a pretty keyboard melody plays, and Bennington screams. The crying woman appears to be in an abusive relationship, and the scrawny singer, his hair in peroxide-blond spikes, seems to narrate her emotions. His chorus—“crawling in my skin / these wounds, they will not heal”—is a strained roar, truly volcanic. His verses are soft and mannered. “Against my will, I stand beside my own reflection,” Bennington sings, looking into the woman’s face. Her nose is pierced, as is his lip.

Professional critics found such works mawkish, and heavy-metal purists dissed Linkin Park in crasser terms—gay or, yes, girly. That’s because, for all its testosterone rage, the band violated the notion that to be male is to be steady, unstudied, and tough. Linkin Park’s form of nu metal—the rap-rock style in vogue around the turn of the millennium—was polished and, for the band’s first few albums, notably devoid of swearing. The musicians were genre benders, stitching patches of hard rock, hip-hop, and new wave to a veil of soft, velvety pop. They had young fans and female fans, and young female fans. And they had Bennington: capable of lullaby gentleness and perpetually fixated on his own victimhood.

This blend, rather than betraying the history of emotionally aggrieved popular music, fulfilled a tradition of complicating the ideal of strong, silent masculinity. Look back at Rolling Stone’s 1969 pan of Led Zeppelin I, which described the high-pitched wails of the lead singer, Robert Plant, as “foppish.” Punk balked at prescribed roles and reveled in sexual transgression. New wavers like Depeche Mode knit the supposedly frivolous and fey sounds of disco into their gloom. Rock misogyny remained alive and well, but these maneuvers encouraged men to communicate in ways that would previously have gotten them labeled wimps.

Grunge, the scruffy rebellion of the early ’90s, most clearly embraced the political potential of such an evolution. The scene was no less male dominated than many rock scenes before it had been, but its practitioners’ moans conveyed a sense of chafing against bodily constraints and cultural expectations. In grunge, the critics Simon Reynolds and Joy Press heard “castration blues, the flailing sound of failed masculinity.” A song like Soundgarden’s “Big Dumb Sex” brutishly satirized the previous decades’ hair-metal machismo: “I’m going to fuck fuck fuck fuck you!” Nirvana’s roaring disdain for the social hierarchies of Reagan-Bush America was conveyed both in Kurt Cobain’s sarcastic lyrics and in his onstage cross-dressing. Sonically, the songs thrived on dichotomies of loud/soft and pretty/grating; the effect was less to gild aggression with sweetness than to wring drama and verisimilitude from the feeling of internal conflict.

The drama was rowdily amplified by the nu metallers of the late ’90s and early 2000s, who experimented with rhythmic contrast by placing swampy funk and break-danceable beats amid the thudding of metal. If the results were ugly, so was the subject matter: pain and trauma, expressed in even more personal terms than before. Ditching the fantastical blather of classic metal and the poetic abstractions of grunge, Jonathan Davis of Korn addressed his own childhood molestation by a babysitter by literally sobbing throughout 1994’s “Daddy.” Grown men confessing experiences of violation, real or fictional, thereafter became a nu-metal trope—though in many cases accompanied by a dose of bellowed machismo. Think of Limp Bizkit’s breakout hit, “Nookie,” a lewd kiss-off to a girlfriend who treated the singer, as he told MTV, “like shit.”

The emergence of PG-rated Linkin Park in this context was so exquisitely well timed, it invited theories that the band had been focus-grouped into life. Bennington and Shinoda’s lyrics cannily rendered rage and alienation in generic terms, staging battles between an “I” and a “you,” who could be a girlfriend, a parent, or something more nebulous. Yet real feelings roiled. Fans often talked about how Linkin Park helped them through their struggles. And interviews with Bennington made clear where some of his own pain came from, and that it was no pose.

When he was about 7, an older friend had begun molesting him. “I was getting beaten up and being forced to do things I didn’t want to do,” Bennington told Kerrang magazine in 2008. The sexual abuse continued for another six years, but he remained silent about it. “I didn’t want people to think I was gay or that I was lying,” he said, hinting at the cost of chasing certain masculine ideals.

Instead of seeking help, Bennington turned to drugs and alcohol. A cycle of addiction, recovery, and relapse continued through two marriages, the births of six children, and a multiplatinum music career. Not long before the 41-year-old hanged himself at home in Southern California last July, he’d told friends he was struggling not to drink. An autopsy found alcohol in his system.

By then, Linkin Park’s heyday as a hit-making force was long past. It had ended in the aughts, and for nearly a decade, nu metal was rarely mentioned by mainstream critics or forward-thinking musicians. But whether or not the new forces on the scene—the likes of Skrillex and Lady Gaga—were Linkin Park fans, the band had clearly previewed the new millennium’s pop sensibility: bombastic, melodramatic, and self-consciously genre busting, though always outfitted with glimmering synthetic textures. Meanwhile, Drake’s rise to stardom represented a breakthrough for male sensitivity in hip-hop, on display in an aesthetic swerve toward sinuously hybrid songs in which rap bleeds into singing against purpled and luminous soundscapes. Though they might not admit it, some of Drake’s fans were surely reared on Linkin Park.

Indeed, in retrospect Linkin Park stands out as a significant evangelist for both rock and rap. The band’s merging of hip-hop and guitar music was committed and proud in a way that subgenre peers like Deftones or Korn never really matched. Linkin Park had a full-time singer, Bennington, as well as a full-time rapper, Shinoda, who genuinely cared about his craft’s history—even if he mostly made clumsy additions to it. Between them, two forms of musical (and often male) angst traditions achieved reconciliation: the pathos and self-loathing of rock, and the aggrieved confidence of hip-hop. The band’s songs read as wounded counterpunches against abusers, finding victory in the moment when the dams of internal repression broke. “I cannot take this anymore,” Bennington hissed in the first line of the band’s first single, “One Step Closer,” which built up to a full-blown screaming tantrum: “Shut up when I’m talking to you!”

Within a tight pop framework, the underlying music looked for opportunities to hybridize as well. Songs such as “Crawling” pushed grunge’s dichotomies to new extremes: A synth riff like something you might hear at a crystal-healing meditation harmonizes with guitar feedback that evokes a garbage-disposal jam. My own entry point as a teen was Linkin Park’s hugely popular, Shinoda-produced 2002 remix album, which showcases a surprisingly deep eclecticism. Some tracks intensify the band’s metal edge, others turn the dial toward the airy and orchestral, and many enlist well-respected rappers (Black Thought, Pharoahe Monch, Chali 2na). A smash 2004 EP by Linkin Park and Jay-Z, Collision Course, converted many black kids to rock fandom, as tributes written since Bennington’s death attest.

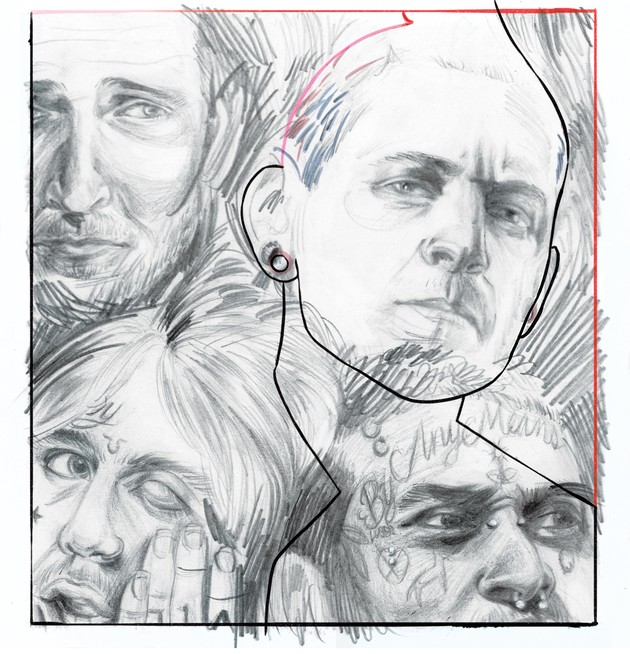

Lately, a wave of stylishly sullen young artists, many in rap, has excavated the painfully unhip, angsty subcultures of the 1990s and 2000s. Bennington’s tragedy further clarified the lines of influence. In one fan video from August 2017, the rapper Lil Peep leads a crowd in black T-shirts in a sing-along of Linkin Park’s “In the End” at an event called Emo Nite. The video is especially moving given that Lil Peep, the 21-year-old Long Islander born Gustav Åhr, died of an overdose a few months after it was filmed. A bisexual fashion-magazine muse with a tattooed face, he seemed to present a plausible future for pop, swerving between melodic hard-rock wails and mumbled hip-hop boasts. And what Lil Peep rapped and sang about, in almost every song, was drugs or suicide. His lyrics sometimes shouted out Cobain, who killed himself at 27 in 1994, and in one music video he glowered in front of a portrait of Amy Winehouse, who died at 27 in 2011.

Dystopian though the thought is, Lil Peep exemplified the arrival of self-annihilation as a trending topic for a new generation of performers who borrow from nu metal, grunge, emo, and punk. The anti-anxiety medication Xanax is to many of today’s rappers what Patrón was to rappers a decade ago, and self-harm is referenced routinely. One breakout duo is named $uicideboy$, and the controversial XXXTentacion, another rising star who loves Cobain, pretended to hang himself on Instagram. “Push me to the edge / all my friends are dead,” went the chorus to Lil Uzi Vert’s 2017-dominating smash. Yet dark emotion is not all that distinguishes this scene. Once again in pop-music history, when hard anger meets soft vulnerability, the commingling almost always comes with a dose of beauty and a jolt of sonic possibility.

It also, once again, comes with troubling and inexplicable real-life associations. Bennington’s death was the latest in a crescendo of shocks in the rock world, following the 2017 suicide of Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell (a close friend of Bennington’s) and the 2015 fatal overdose of Stone Temple Pilots’ Scott Weiland (whose band Bennington had played in). Meanwhile, the morbid preoccupations of Lil Peep and his peers track all too closely with urgent social realities like the prescription-drug epidemic and the rising rate of suicide among young people. It does not seem coincidental that one of the biggest songs of 2017, Logic’s “1-800-273-8255,” measurably increased calls to that phone number, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

In the face of these dark facts, who can avoid pondering some sort of grim transference of inner torment across generations? But it is safer to simply recognize that music responds to the real world in any era because music is created by real people. “These wounds, they will not heal” goes “Crawling,” and the feeling that there is no future has proved true for too many pop creators. At least their music, finding new boundaries to cross and break, escapes that fate.

This article appears in the July/August 2018 print edition with the headline “The Sound of Rage and Sadness.”