In the world of Thai traditional music, there is a highly esteemed competition, known as prachan, in which groups of musicians battle each other to produce the best pieces. The practice resembles a political fight in many ways.

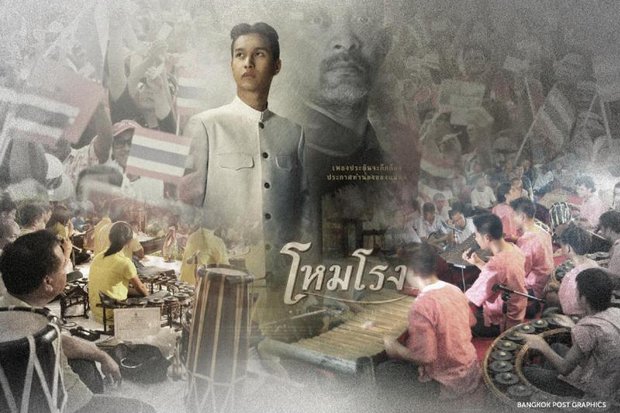

Thanks to Homrong (The Overture), a 2004 film about the life of Thai traditional music maestro, Luang Pradit Phairoh (Sorn Silpabanleng, 1881-1954), the public became familiar with prachan.

The film portrayed prachan as a fight between a protagonist and an antagonist: They possessed different ranaat playing techniques -- one was trained in music of the old school thought and the other embraced new techniques.

One appeared in a white outfit and the other in a black -- a fight between good and evil.

Prachan is a competition that began in the early Rattanakosin era, pitting two pi phat (percussion) ensembles against each other. The ensembles belonged to the old Siamese courts, which played the role of musical patrons. As shown in the film, each prince acquired talented musicians, mostly ranaat eke (high-pitched xylophone) players, who represented the royal courts.

The uniqueness of this practice and the key feature which differentiates it from Western music competitions is that there are no judges to decide who the winner is. The victory is judged by the reaction of the audience -- mainly by their applause.

The 1932 political change saw the end of royal patronage for Thai musicians. Each artist went back to their homes in Bangkok and the provinces and earned livings as musicians. Some established music schools that took in students who wanted to sharpen their skills.

There continued to be intense competition between the well-established schools. With court-sponsored prachan knowledge, the music masters were able to popularise the music genre. Since then, the audiences, mostly ordinary people, have become more familiar with the prachan practice.

The competition can be seen as a fight for symbolic cultural meaning -- a showcase of the proficiency of the musicians and their masters. The more success prachan generated the more the public accepted and were interested in musicians.

Through prachan, we can see the combative culture in music societies and the struggle for musicians to stay on top. Some popular musical ensembles were run by such music legends as Supoj To-snga, while the Duriyapraneet music schools had their own students who sought to become top in music circles.

However, Thailand's traditional music society experienced a major change when this music genre lost virtually all its popularity amid an influx of Western-style entertainment after World War II.

Thai musicians sought places in education institutions and state agencies that played the role of a patron, fielding their respective ensembles as prachan contestants. Under such circumstances, musicians from different schools who had faced each other on stage were forced to work together and had to seek a compromise.

Competitions and fights exist in other areas, not just in the music circle. In politics, we saw ideological clashes between people holding different political views who used colours to represent their political identity.

Like a musical prachan, those on the opposite sides of colour-coded politics struggled to get what they wanted, ranging from desires for equality, justice, status quo, improvement of living conditions, a crackdown on corruption, and power bargaining.

In their tense struggle, the two opposite sides employed various techniques. It can be noted that music became a tool for both sides.

In one incident, as the DSI summoned Abhisit Vejjajiva and Suthep Thaugsuban in 2012 on charges in connection with the crackdown on the red-shirt protests, there was a big gathering of red shirts who played the song Toranee Kansaeng (The Weeping Earth) -- a typical funeral song -- as if to add pressure to the two politicians.

Those on the yellow side, meanwhile, released a video clip, "Greedy Thaksin," with a song containing anti-Thaksin content, accusing him and his family of graft. The music was made in a style similar to that of Yuenyong Opakul or Add Carabao. The musician later pointed out that he had not performed the song specifically for this political purpose. In fact, it was a musical meme from his old work.

We can say the fight between the red and yellow shirts is like a prachan, in a sense that both gave power to the people who were to there to offer judgement. It's similar to a music competition in that there is no jury or judges and there is no strict format or rigid rules to follow. In politics, both sides do everything to get support. They aim to get the vote of the people using a variety of flexible techniques.

But political competition is far more complicated. The long-standing conflict came to a stop when the military stepped in as if it were a judge.

It's ironic that the military in citing "peace and order" and the great people, or Muan Maha Prachachon, breached all the rules while leaving behind a call for equality and freedom. We cannot say that this is what we had hoped for in our quest for a new, better society.

Great Lekakul, PhD, is Senior Teaching Fellow (Music Department) at SOAS University of London. The article which appeared on BCC Thai is an adaptation of his doctorate thesis at SOAS.